News Intelligence Analysis

See Vincent's Bedroom in Arles

From the New York Times

October 14, 2005

Art Review | Vincent van Gogh

The Evolution of a Master Who

Dreamed on Paper

By MICHAEL KIMMELMAN

SHORTLY after he landed in Provence in February 1888, Vincent

van Gogh wrote to his brother, Theo, about a beautiful sight.

He had spotted "a ruined abbey on a hill covered with holly,

pines and gray olives." It was the old abbey on Montmajour,

a crumbling fortress and tower atop a rugged outcropping with

an immense vista of vineyards and wheat fields. By July, van

Gogh climbed the hill. The mistral, the strong seasonal wind,

had kicked up, making it impossible for him to plant an easel

and paint without his canvas shaking uncontrollably, not to mention

the mosquitoes that the wind swept in.

But van Gogh boasted to Theo that while "not everyone would have the patience," he could draw. Made with a scratchy reed pen on large sheets of Whatman paper, his Montmajour drawings come about two-thirds of the way through the survey of van Gogh's drawings now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

They translate sky, rocks and plains into a swarm of swirls, dots, jabs and scratches. Foaming, cable-knit patterns imply the heaving gusts of wind rustling olive branches and bending gnarled olive trunks; whispery, microscopic speckles, endless numbers of them, mimic the quality of dull light on receding fields as they evaporate into the horizon. You can even sense color - the dark brown of the earth, the yellow and lilac fields and gray-blue sky - in van Gogh's black and white.

![]() To

say these pictures required a kind of monkish devotion to draw

is in part to reiterate his inherited Dutch Reform ideas about

nature and the revelation of God. Nature was virtually supernatural

to him. There is no better proof that he wasn't the mad hatter

of movie legend than these painstaking tributes to sublime countryside

- as Robert Hughes once put it about van Gogh's paintings, "if

sanity is to be defined in terms of exact judgment of ends and

means and the power of visual analysis."

To

say these pictures required a kind of monkish devotion to draw

is in part to reiterate his inherited Dutch Reform ideas about

nature and the revelation of God. Nature was virtually supernatural

to him. There is no better proof that he wasn't the mad hatter

of movie legend than these painstaking tributes to sublime countryside

- as Robert Hughes once put it about van Gogh's paintings, "if

sanity is to be defined in terms of exact judgment of ends and

means and the power of visual analysis."

You can still picture van Gogh, bookish and fastidious, pouring out his thousands of letters and drawings, private diaries in words and images, sent to his brother and to a few trusted friends, providing him with a stability that he evidently could find nowhere else in life. The Protestant preacher's son, he dutifully recorded his constant labors with pen and paper.

Does it seem that there's always another van Gogh show in town? The last full-fledged van Gogh exhibition at the Met actually happened nearly two decades ago.

"Van Gogh in Saint-Rémy and Auvers" (1986) came on the heels of "Van Gogh in Arles" (1984) - almost absurdly popular events, culturally apotheosizing the whole Reagan-era enthrallment with conspicuous consumption. Those twin blockbusters roughly dovetailed with the indelible spectacle of enraptured Japanese investors, on the eve of the last art market meltdown, lobbing billions of yen at any old Impressionist picture, above all on everything associated with the holy one-earlobed Dutchman.

Poor Vincent. First it was Kirk Douglas. Then it was the din of the throngs and the ka-ching of the cash registers, totaling up asylum postcards and Sotheby's profits, the reverberations still audible a generation later, like radio waves traveling through space, so that it can seem like the van Gogh shows never end. Our hackneyed star-crossed patron saint of unrecognized genius, he remains art's favorite martyr, expiating our cultural sins, calling forth the blind and the faithful to the temple on Fifth Avenue.

And now he's back for this survey (it's already open to museum members, and opens Tuesday to everyone else), which includes a few related paintings that illustrate how he moved between one medium and the other. Organized by Colta Ives and Susan Alyson Stein of the Met, and Sjraar van Heugten and Marije Vellekoop of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, the exhibition is thorough and dense. If, 20 years ago, it was difficult to glimpse his canvases through the mobs, it will probably be harder still to appreciate these works, with their obsessive particulars and increasingly nuanced feelings.

But I suggest you think again before deciding you've got a case of van Gogh fatigue and skipping the occasion. This is not just because the focus here is on drawings, which are on the whole less iconic than the paintings, but were so important to him and to the early spread of his reputation. As they say, in the flesh great art, no matter how often it has been dully reproduced or mistaken for a price tag or overrun by crowds, somehow retains its dignity and originality. It slows your system and demands that you stop and look afresh.

![]() And

here, before the work, you can find yourself swept back to wintertime

in a melancholy grove of pollard birches at Nuenen; to dawn on

the beach beside the slender, spiky sailboats at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer;

to the shady vestibule of the asylum at Arles, where the double

doors open onto the sunny garden, as if onto Eden; and to the

cobblestone Place du Forum at night, in the gaslight glare of

the Café Terrace.

And

here, before the work, you can find yourself swept back to wintertime

in a melancholy grove of pollard birches at Nuenen; to dawn on

the beach beside the slender, spiky sailboats at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer;

to the shady vestibule of the asylum at Arles, where the double

doors open onto the sunny garden, as if onto Eden; and to the

cobblestone Place du Forum at night, in the gaslight glare of

the Café Terrace.

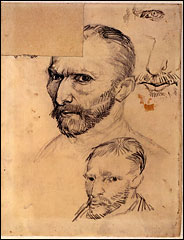

Haunted sights, and familiar people: the beloved Zouave, with "a small face, a bull neck, and the eye of a tiger," as van Gogh told Theo, whose brocaded jacket and its encroaching pattern of curlicue vines makes him into a kind of mustachioed Daphne. And of course, Vincent himself, glowering at us out of the corner of his eye, with a third eye drawn above him, hovering like a Masonic symbol, as if his own gaze were not disturbing enough.

Frankly, the whole show, even including the bad drawings, is unforgettable.

It tracks the arc of his transformation, in a decade, from a tedious, disingratiating illustrator of glum peasant scenes into a fluent draftsman. There was, as you see early in the Met show, no reason to believe that he would be good. Initially, his tight attempts at figures, like the elderly man seated before a fireplace, or the old woman sewing, border on the hilariously hamfisted.

He had foundered for a decade as an art dealer, teacher, bookseller and freelance evangelist among Belgian coal miners. When he took up art as a career in 1880, at the age of 27, he was desperate to make up for lost time. But the process turned into a long, hard slog. He devoured instruction manuals, adopted a wood perspective frame, which he lugged around, to aid him when he drew landscapes. And he emulated English illustrators, Rembrandt, and French painters like Millet and Breton, oblivious, until the mid-1880's, of Impressionism.

This paid off, not in the obvious way. The first gallery at the Met culls the best of his early drawings, such as they are, and van Gogh, divorced from the cutting edge, left to his own devices, gradually makes peace with his own awkwardness. Landscapes achieve a strange, gloomy grandeur. A drawing of a peasant woman gleaning, from 1885, just before van Gogh went to Paris, is clumsy, a near abstraction that suggests a half-shucked ear of corn. But the effect now looks deliberate. It's not surprising to learn from the show that Degas acquired this drawing, which clearly reverberates with his own late nude bathers and their exaggerated anatomies.

"Tell him that I should be in despair if my figures were 'correct,' in academic terms," van Gogh wrote after a fellow artist complained about the distortions. "I don't want them to be 'correct.' Real artists paint things not as they are, in a dry analytical way, but as they feel them. I adore Michelangelo's figures, though the legs are too long and the hips and backsides too large. What I most want to do is to make of these incorrectnesses, deviations, remodelings, or adjustments of reality something that may be 'untrue' but is at the same time more true than literal truth."

![]() The

remark could be the manifesto for modernism. Once in Paris, swept

up by the new radical painting, by Japonism and by fresh subjects,

van Gogh quit drawing briefly. But in Arles, he returned to it

with a mission. He ditched the perspective frame. The Arlesian

landscape, with its patchwork of fields, echoing Holland and

the flat, interlocking planes of Japanese prints, liberated him.

Reeds, plucked from the Midi fields and sharpened into pens that

could hold only a little ink at a time, encouraged him to devise

an all-over, rapid sort of notation, a Morse code, which he endlessly

varied.

The

remark could be the manifesto for modernism. Once in Paris, swept

up by the new radical painting, by Japonism and by fresh subjects,

van Gogh quit drawing briefly. But in Arles, he returned to it

with a mission. He ditched the perspective frame. The Arlesian

landscape, with its patchwork of fields, echoing Holland and

the flat, interlocking planes of Japanese prints, liberated him.

Reeds, plucked from the Midi fields and sharpened into pens that

could hold only a little ink at a time, encouraged him to devise

an all-over, rapid sort of notation, a Morse code, which he endlessly

varied.

After painting boats at sea, for example, he dashed off, as advertisements for himself, drawings of the same painting. For Émile Bernard, he drew the scene with roiling waves; for John Russell, with calmer waters; for Theo, in a mood subtler still. Each was completely different. As he kept reinventing drawing, he also found himself.

And by the time he reached the asylum at Saint-Rémy, he was recording everything in drawings that breathe light and air. Unloosed, they attain a newfound, almost musical grace. Nesting curls represent the flickering flames of cypresses and their rich color: "a splash of black in a sunny landscape," as he wrote, "one of the most interesting black notes, and the most difficult to hit off exactly."

The show ends with farmhouses and fields in the northern town of Auvers: billowing clouds of coiled, toppling lines, like tumbling putti, made with watercolors and oils, imitating the staccato patter of reed pens. In an old vineyard, under a baby blue sky, chickens scratch in the cool shade of a pergola. Van Gogh sketched this not long before he shot himself, when, he told Theo, "I still love art and life very much."

It is the accomplishment of somebody who finally discovered how to make the hardest thing he had ever tried to do look easy.

Talk about a beautiful sight.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company

Send a letter

to the editor

about

this article

This article is copyrighted material, the

use of which has not been specifically authorized by the copyright

owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to

advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights,

economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc.

We believe this constitutes a 'fair use' of any such copyrighted

material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law.

In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material

on this site is distributed without profit to those who have

expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information

for research and educational purposes. For more information go

to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes

of your own that go beyond fair use, you must obtain permission

from the copyright owner.