News Intelligence Analysis

From the New York Times

January 7, 2005

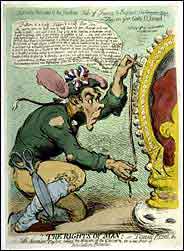

ART REVIEW | 'JAMES GILLRAY'

![]() British Political Cartoonist in Era of

the Enlightenment

British Political Cartoonist in Era of

the Enlightenment

By KEN JOHNSON

Most art has a limited shelf life. Minor forms like caricature

and political cartooning are especially perishable because they

depend on the viewer's familiarity with forgotten topics and

personalities. The contemporary caricaturist David Levine, for

example, is a fine draftsman, but the excitement of his drawing

is mainly in the way it transforms the features of public luminaries

we know well through photographs. Will his art be as compelling

when his subjects have faded from memory?

That satiric visual journalism can transcend its time has been proved. (See Goya's "Disasters of War," for instance.) And there are examples in an exhibition of prints by the English satirist James Gillray (1756-1815) at the New York Public Library that cross the line between interesting artifact and still-exciting art.

One of the most popular cartoonists of his day, Gillray produced lively, hand-colored etchings that lampooned major political figures, including the king, the queen, the prime minister and Napoleon, and many minor ones, too. With fearless, exuberant contentiousness, he tackled the French Revolution, England's war with France, high taxes, domestic unrest, fear of foreign invasion, Irish rebels and conflict between the Whigs and the Tories. (He mostly favored the Tories.)

Gillray's prints were purchased by people of means, even the Prince of Wales, one of his targets. Later in the 19th century, Samuel J. Tilden, a New York governor and presidential candidate, amassed a nearly complete collection of Gillray's works, which was eventually bequeathed to the New York Public Library. Roberta Waddell, the library's curator of prints, selected about 160 pieces from the Tilden collection for the current exhibition.

Viewing this show is something of a challenge. If you are

steeped in late 18th- and early 19th-century English history,

you will probably find it enthralling from beginning to end.

Accompanying every print is a substantial label describing its

characters and explaining the narratives and situations, which

in most cases would otherwise be mystifying. Viewers not up on

their history may be e

![]() xhausted

by all that reading, however necessary and educational. This

is a show that needs a well-illustrated and annotated catalog.

xhausted

by all that reading, however necessary and educational. This

is a show that needs a well-illustrated and annotated catalog.

It is a problem, too, that there are so many works, not all warranting the attentive examination of symbolic and narrative details and inscriptions that cram each picture. Gillray was trained as a professional engraver and studied drawing at the Royal Academy; technically, his prints are invariably excellent. He also possessed a high degree of visual literacy and often parodied paintings by famous artists. But as you proceed chronologically through the show you may feel disappointed by the heavy-handed, conventional cartooning in the early works. All the people he mocks by making them fat, ugly and idiotic tend to look as if they belong to the same family.

As time goes by, however, Gillray's drawing becomes more sensitive and particularized, his scenarios more surprising and ambitious. Sometime around the mid-1790's, his art takes flight, and the effect is exhilarating. His best works, pictures teeming with dozens of characters great and small, call to mind proto-Surrealists like Hieronymus Bosch, William Blake and James Ensor. You may even think of the best satiric cartoonist of our time, R. Crumb.

"End of the Irish Farce of Catholic Emancipation" (1805) shows a wild scene of three British leaders literally blowing down a procession of characters in Roman Catholic regalia approaching St. Peter's heavenly gate, which is labeled "Popish Supremacy." As the frightened and angry pilgrims - all identifiable supporters of Catholic emancipation - tumble this way and that, small, finely rendered liturgical and other sorts of objects fly through the air. It is a burlesque comedy full of religious prejudice, but its swirling composition, masterly control of light and shadow, and extraordinarily prehensile draftsmanship raise it far above its lowly conceptual origins.

"Great Breeches" is a Bruegelesque seaside vision centered on the miraculous spectacle of a pair of monumental, upended, semitransparent, big-bottomed trousers, within which there is a miniature scene of gluttons feasting around a big table. At the foot of the pedestal that the breeches are mounted on, rats infest a bed of roses; Napoleon looks down from a distant cloud. The imagery has to do with complicated tensions in British party politics, which included a faction called the Broad-bottoms. But whatever its topical contents, it is a wonderfully provocative visual fantasy.

There are some later works that look as though they were made under the direct influence of Blake. In "Phaeton Alarm'd," for example, a Blakean hero driving his chariot across the heavens is attacked by monstrous characters derived from the zodiac and the constellations, all bearing the recognizable heads of contemporary politicians. (Some early works, by the way, are modeled on pictures by John Henry Fuseli, the Swiss-born painter of weird visions.)

One of Gillray's most famous images is the uncharacteristically simple "Gout," which depicts a ferocious little black devil attacking a large, fat and throbbing foot. It is like one of Blake's visions of a minor demon.

When Gillray died in 1815, he was, according to an essay by Ms. Waddell, "incurably insane." This may tempt some to wonder whether his adventures in pictorial lunacy were in any way connected to his final psychological condition. Was the tension between social cynicism and an extremely fertile imagination too much for his mind to bear? Little is known about his personality, however, and it makes just as much sense to view his achievement as a high-water mark of Enlightenment-era sanity.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company

Send a letter

to the editor

about

this article

This article is copyrighted material, the use of which has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a 'fair use' of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond fair use, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.